Of all the memorable visual flourishes in the original Star Wars, there are two images that stand out. The first is arguably the most iconic — Luke Skywalker, gazing off at the horizon, as the twin suns set on Tatooine. It represents the promise of adventure, the enormous world that waits beyond the garden gate, and serves as the prelude to his epic journey.

But the second is much simpler. It’s Luke, Leia, and Han, arm-in-arm and filled with joy, as they celebrate their victory over the Empire back at the rebel base. That moment underlines their unlikely friendship, borne out of shared struggles and triumphs, and shows the film’s heart, clearly felt even in the midst of this grand adventure. That contrast is what Star Wars, at least in its original form, comes down to, and what makes the film still so salient and impressive nearly forty years after its release.

There is a breathtaking scope to the film that’s built up organically. A New Hope hints at a tremendous ecosystem of people, planets, and politics beyond the protagonist’s ambit. And bit-by-bit, writer-director George Lucas brings his hero, and the audience, onto that grander stage. The reach and complexity of the universe Lucas and his colleagues created are conveyed as much through the images they crafted as in the film’s dialogue.

Lucas’s script, of course, gives the viewer breadcrumbs about The Force, and the state of intergalactic diplomacy, and other sundry-yet-enticing details about this galaxy far far away. But more than anything spoken, when the film focuses on the motley collection of creatures in the Mos Eisley cantina, or on the vast, beautiful spacescapes that establish the setting, or on the massive star destroyers and tiny rebellion ships in their wake, the audience feels the details of this world in a visceral way that words cannot capture.

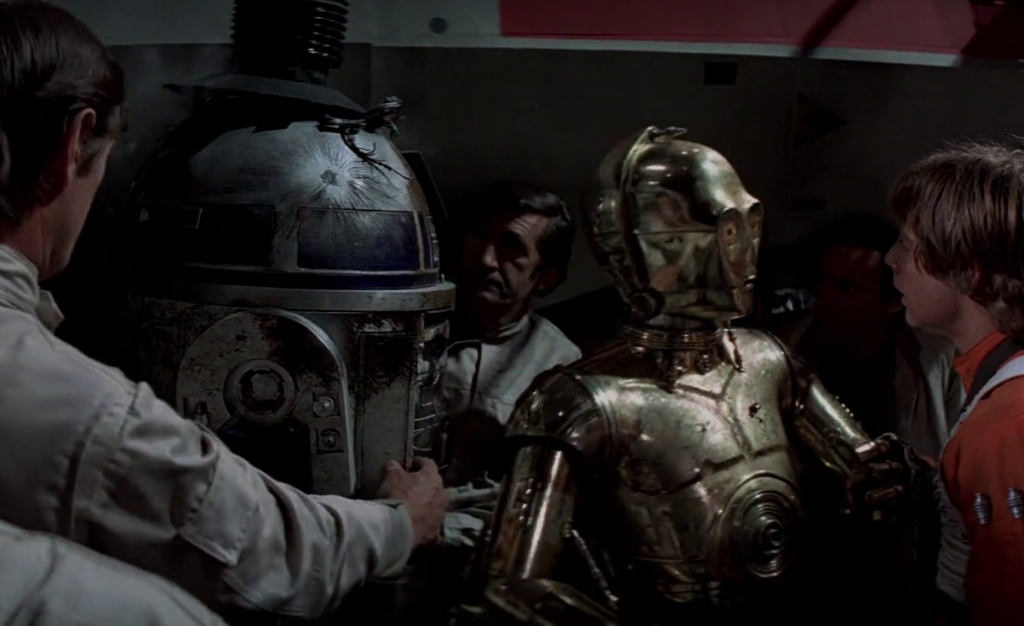

To some degree, the aesthetics tell the story, and communicate the differences in power and strength between the Empire and the Rebellion without needing to make them explicit. Much has been made, rightly, about the “used future” look of the film. The droids who roll and stumble through spaceships and deserts look worn when we see them up close. The domain of the Rebels is full of tan and brown and beige, like the grit and grime that seems to have covered every inch of their environment. Their world, appropriate to Disney’s current ownership of the property, is a small one. In contrast, the world of the Empire is one of sharp blacks, and whites and grays. In the scenes set on the Death Star itself, there are towering generators, and enormous installations within the floating fortress. When the junked out Millennium Falcon is dragged inside, it clashes with the straight lines and rigid perfection of the imperial fleet and the crown jewel of the Empire’s war machine.

That backdrop helps to make Luke’s journey feel appropriately big and important. The breadth of his journey–from a worn-down moisture farm to the wild diversity of Mos Eisley to the daring rescues and dogfights of interstellar travel–expands at the same time Luke’s perspective does, and the production and design sets the stage for that growth.

By the same token, John Williams’s score conveys the magnitude of the tale being told in its orchestral splendor. While Star Wars is often surprisingly willing to forgo music and allow the actors and imagery to convey the mood of a scene, the moments where Obi Wan waxes philosophically about the force, or Luke looks off into the distance and years for adventure, or our heroes are honored for their brave deeds, the swell of Williams’s orchestra sets the tone, and can still give me chills all these years later.

But the counterpoint to this grandiosity is the smaller, personal stakes in the relationships between Luke, Leia, and Han. What keeps this world-spanning space opera from feeling too cold or impersonal is the realness and warmth of those characters. The idea that a farm boy, a smuggler, and a princess could find common ground and forge a friendship is an endearing one, and it gives shading to the broader conflict that A New Hope depicts.

George Lucas has been, not unfairly, maligned for the dialogue he writes. Yet, that makes the ever-present humanity of the film’s performances all the more impressive. It’s clear that the kind of language and rhythms Lucas employs in A New Hope are meant as a throwback to the affected tones of the Flash Gordon serials to which he pays tribute in Star Wars. But the cast of the film gives such life to his words that they’ve become indelibly etched into the cultural edifice.

Harrison Ford shines with roguish charm as the delightfully rough-around-the-edges Han Solo. There’s a sweaty, improvisational vibe to his performance, and it sells Han’s role as the noncommittal outsider, adding stakes to his eventual return to help save the day. Far from being a mere damsel-in-distress, Carrie Fisher’s Leia has a defiant edge to her, that makes the character distinctive. Leia is just as likely to upbraid Luke and Han for not thinking things through, or to take matters into her own hands, as she is to be bland and passively grateful for their help. It makes her a full-fledged equal to the other heroes of the film. And Mark Hamill’s Luke, easily the most traditional, white-bread character of the three, still conveys the honesty of the young Skywalker’s desire for something more in his life, and an inherent goodness within him.

But despite this, or rather, because of this, they bicker! And disagree! And snipe at one another when they’re forced to work together! And yet, eventually, they help each other and find themselves bonding amid their squabbles and difficulties. It’s one of the film’s greatest strengths.

What’s more, that bent toward showing the characters sparking off one another extends beyond the main trio. Han laughs and lightly resents the kindly-yet-stoic Obi Wan and his various schemes and philosophies. The Imperial leaders on the Death Star verbally joust and debate, doubting even the sonorous and imposing Darth Vader himself. C3PO and R2-D2 sound like an old married couple, each constantly needling the other. But that just helps these characters to feel real within a fantastical setting, and makes the later moments–like when C3PO pleads with the rebel leaders ensure that R2-D2 is repaired after the Battle of Yavin–more meaningful.

It also gives power to the found family forged by Luke, Leia, and Han. These people who don’t know each other set aside their differences to do what’s right and fight for the greater good of the galaxy. And despite their differing backgrounds and philosophies and personalities, they come together. It’s what makes A New Hope more than just a thrilling adventure, but also a story of genuine human connection.

Apart from these broader elements, other little details stand out when watching Episode IV front-to-back for the first time since childhood. A New Hope seems far more deliberately paced as an adult. This lends to the epic feel of the film, but also means that the movie takes a little time to move from act-to-act. Also, the Special Edition edits to the film, which completely escaped my notice as a child, now stick out like sore thumbs. The aesthetics of the film, and the world that Lucas and his collaborators put together, reflect a certain worn beauty; the Playstation-level CGI pasted into that setting is jarring and discordant.

But again, the original Star Wars is a film about grand events contrasted with the smaller moments that make it all matter. A New Hope is the culmination of both the buzzing hive of a spaceport, and the solitary farmhand gazing off at the horizon; of a thrilling, intricately-crafted dogfight in the vast reaches of space, and of a lonely escape pod drifting below it all; of the terror of the Empire destroying an entire planet, and the more intimate evil of Vader slowly choking the life out of one of his co-conspirators; of the light-scattering explosion of a massive space station, and a simple moment of jubilation between friends. Star Wars is the great and the small, the incredible and the mundane, the breathtakingly huge and alien, and the endearingly simple and human. And that’s what makes it awe and resonate even today.

Pingback: Star Wars: The Force Awakens Is Like a Great Cover Song | The Andrew Blog