Cars is easily Pixar’s most poorly-received film. The movie, featuring a world of anthropomorphic automobiles, completely rankled fans of the studio. These detractors view Cars as a rare misstep amidst Pixar’s otherwise unblemished offerings. While movies like A Bug’s Life may have underwhelmed, and those like Ratatouille flown under the radar, no Pixar film has engendered as strong a negative response from the faithful as Cars. With a sequel coming out soon, these doubters have renewed and redoubled their critiques.

Personally, I generally enjoyed the film as a bit of harmless popcorn entertainment, and I believe that Pixar is, in many ways, a victim of its own success. The studio has a remarkable track record of releasing uniformly outstanding feature films, from its initial offering of Toy Story to classics like Finding Nemo to recent triumphs like Up. When held up against these lofty brethren, Cars status as merely “pretty good,” makes it seem overly lacking by comparison. It’s a solid, but unspectacular film, doomed by the company it keeps.

That said, there are plenty of good reasons to walk out feeling nonplussed about Cars. The story is far more standard and predictable than your average Pixar release. The studio is known for taking risks with off-the-wall plots and oddball, offbeat characters. Cars hardly qualifies. Your average viewer, even the ones still asking for Happy Meals, knew pretty quickly that Lightning McQueen would recant, learn the value of community, and mend his reckless ways. On top of this, many of the characters in the film are fairly one-note. They lack the depth or endearing nature of your typical denizens in a Pixar universe. Cars can boast one or two touching moments, but overall the film is much more of a mere enjoyable ride than a heartwarming journey.

Then, there are the more “meta” reasons to dislike the film. Many object to the fact that the franchise appears to be far more merchandise-driven than story-driven unlike the usual Pixar offerings. The fact that the film managed a sequel, due in large part to the fact that it was a merchandising juggernaut for the studio despite the tepid critical reviews, rightly frustrates many Pixar fans. What’s more, Larry the Cable Guy, the voice of wacky sidekick “Mater,” definitely rubs a plenty of individuals the wrong way. The truth is that he’s perfect for a kids movie, since his act plays roughly to the level of your average five-year-old. Still, for adult viewers of these films, he can certainly be grating and the propagation of his style of comedy can be enough to turn anyone off the film.

Though your mileage may vary (see what I did there?) these are all valid criticisms. One criticism, however, comes up again and again in the discourse about this film, and it is the stupidest reason to take issue with a kids movie. It comes down to the detractors who debase the movie over one simple question: who built the Cars?

The line of questioning is fairly predictable. “Who made these vehicles?” “How do they reproduce?” “Where are all the humans?” “How did they come to be?” “Pixar never explains any of this, and it makes the movie totally unrealistic and unbelievable.” It’s all variations on a theme. An acquaintance of mine puts the criticism this way:

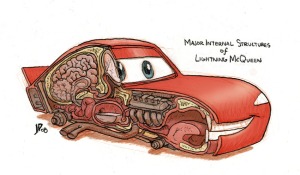

Artist Jake Parker's interpretation of the physiology of the Cars. You can see more of his work at http://agent44.com/blog2

“It raises the question of whether these are cars that became sentient, or if they’re just biological beings. If so, what evolutionary purpose do the seats have? I figure there’s some way they could [have] reproductive car sex somehow, there’s lots of parts on a car that you could imagine would do that, but why would they have seats?

So maybe they are just cars that became sentient, but if so, what the hell’s going with that? So there’s just a bunch of sentient cars that formed a society somewhere? Somewhere where there was a city for some reason? Did they just find it, or did they build it themselves. Is there a whole planet worldwide where cars were able to build things?

I guess maybe a couple of these questions would be answered in the movie, but I’m assured that most of them aren’t, which is dumb because the questions it raises seem like they’d make a far more interesting film. Even Dreamworks tend to put more thought into their universe’s own internal logic.”

There’s plenty of good reasons to dislike Cars, but this line of criticism is absolute nonsense. You can ask the same sorts of questions with respect to any of Pixar’s most beloved films. How can toys move with no muscles? How can they think and feel and emote without brains? Is there some wizard’s spell that made them all sentient or is it just a sci-fi-esque conspiracy by the Mattel corporation? Additionally, how could a rat understand English? Or learn how to cook? Or control someone just by pulling their hair? Furthermore, how did there come to be a separate dimension of Monsters? How do they reproduce or develop into all these different forms? Are Mike Wazowski and his girlfriend in an interspecies relationship? None of this is ever explained and the “internal logic” of these films manages to hold up just fine.

It’s a bloody kids movie; that’s why. Cars‘s central premise is no more fantastical or unreasonable than those of the other members of its ilk. There’s no good reason why people are so ready willing and able to give all other childrens movies a pass on this sort of thing, but are so quick to level the “who the hell built them?” criticism at Cars.

Even taking it outside of Pixar: The Brave Little Toaster stars a cadre of moving, talking, household appliances. The Nightmare Before Christmas features the existence of several holiday-themed lands with no explanation for how or why they’re there. Nearly every Disney movie includes an animal sidekick or two who are far more anthropomorphic than realistic. Heck, take the principle Disney universe for example. How is it that Mickey Mouse owns a dog, but one of his best friends is also a dog? Is Pluto part of a subjugated class that Goofy managed to escape from? How did all these human-esque mice and ducks and dogs come to form a society and live together? More importantly, who cares?

The upshot of all this is that this is the silliest sort of reason to take issue with a movie. It’s certainly funny to consider the little conceits of the genre that are often present in kiddie fare – the Smurfette discussion in Donnie Darko is a great example – but no one legitimately faults these shows or movies for them, and for good reason. It’s called willing suspension of disbelief, and its essential to almost any enjoyable viewing experience, particularly those involving material at least nominally directed at children.

A house can fly using only helium balloons. A magic genie can help a street urchin become a prince. A pack of lions have the mental wherewithal to essentially recreate Hamlet. We’re willing to buy into all of these fantastical premises because no matter how outlandish their setups, they all tell a great story. And if your approach to Cars involves getting stuck on their origin of species, then you’re missing the point.

No, we don’t know how the Cars came to be. We don’t know who built them, or how they reproduce, or how their society and culture evolved into its present state. They come onto the scene, fully formed, as devoid of explanation as Woody or Sully or Remy. We don’t demand to know the origins of these others characters, nor should we. Children’s movies often provide a glimpse into fanciful worlds, where the usual rules of realism are bent or even broken. This is a feature, not a bug, and it allows us to take a full view of the creator or creators’ imagination and wonder.

We need not be bogged down by the details. It’s true, there is something endearing about an intricately-crafted world. One of the reasons that the Harry Potter series has enjoyed such success is that readers find themselves drawn into the magical ecosystem that J.K. Rowling has created. Still, not every work needs to delve into a complex and elaborate back story. Often times, works intended for children feature magical or outlandish elements that, in fact, defy explanation. That’s the point. Whimsy is self-justifying.

The question is ultimately whether you, as the viewer, find yourself compelled by the story and the characters. No matter how fantastical the setting, from the otherwise mundane setting of Toy Story to an entire universe of science fiction and fantasy in Star Wars, a good creative mind can make anything work. The point of most films isn’t how the characters got there, but what they do once they’ve arrived on our screens. Cars is no exception. It’s a film that certainly has its problems, but the fact that it features an imaginative world of talking automobiles isn’t one of them.

13 Responses to Why “How Were They Built?” Is the Dumbest Criticism of Pixar’s Cars