-

Recent Posts

- Better Call Saul: There Are No Happy Endings between a “Rock and Hard Place”

- Black Widow Keeps It in the Family for Natasha’s Last Ride

- Loki Finds New Purpose in the Man behind the Mischief

- In its Debut, Star Wars: The Bad Batch Decides Whether to Obey or Rebel

- Nomadland: A Film Out of Time, For Our Times

Archives

Recent Comments

- Ed Clarke on Contact

- Matt on Why “The Frying Game” Is a Dark Horse Contender for The Simpsons’s Worst Episode Ever

- Lilly Dow on Contact

- Stacey on Veep’s Series Finale and the Hollowness of Getting What You Want

- Evan Jaocbs on Contact

Meta

Category Archives: Movies

The Martian Is a Feel-Good Movie that Earns Every Bit of the Feeling

Despite a number of well-crafted elements, the success or failure of The Martian absolutely depended on Matt Damon’s performance in the lead role. It’s true that, in contrast to spiritual predecessors like Gravity and Castaway, the film was not a one-man show, instead featuring a murderer’s row of stellar supporting players. What’s more, its narrative thrills were not limited to its protagonist’s adventures on Mars; The Martian told an equally compelling story of what was happening back home.

But Damon’s Mark Watney, and his lonely trials and tribulations on a desolate planet, were the lifeblood of the film, commanding the lion’s share of its run time and focus. That meant that for much of the movie, Damon alone had to convey his character’s distress, his resolve, his humor, and his humanity, with no one but the camera to talk to. And despite that handicap, he succeeded with flying colors. Few major roles share the degree of difficulty of Damon’s here, where the main character spends much of the film in solitude, with little in the way of major plot developments or action to maintain the energy of the picture, and the performance Damon delivered with that backdrop more than lived up to the challenge.

Posted in Movies, Prestige Pictures, Sci-Fi Movies

Tagged Drew Goddard, Matt Damon, Movie Reviews, Oscars 2016, Ridley Scott, Science, Science Fiction

Leave a comment

The Hateful Eight Is Quentin Tarantino’s Meditation on Justice, Tribalism, and Identity

Caution: This review contains major spoilers for The Hateful Eight.

The Hateful Eight is filled with characters who are constantly performing for one another. Some of them are pretending to be something they’re not in the hopes of avoiding detection, some tell tall tales with theatrical enthusiasm in order to provoke, while others embellish at the margins to puff themselves up or knock someone else down. It’s no grand reveal when discussing a Quentin Tarantino movie to note that more than a few of them meet a bloody end, but what’s striking about the director’s eighth film is the way that the personas his characters assume, what roles they inhabit and which factions they align themselves with, change the kind of consequences they face within it.

The Hateful Eight is a film about justice and tribalism and how those two concepts inevitably lead to some strange, unsettling outcomes when combined. At the same time, the movie is just as concerned with how the identities that we project affect the kind of “justice” we receive.

Posted in Movies, Prestige Pictures

Tagged Justice, Movie Reviews, Quentin Tarantino, Samuel L. Jackson, Westerns

Leave a comment

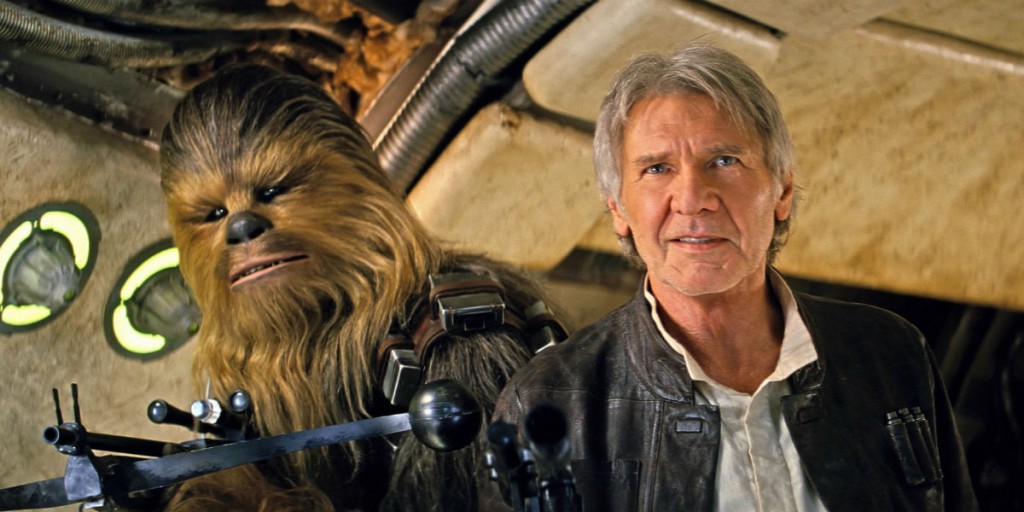

Star Wars: The Force Awakens Is Like a Great Cover Song

CAUTION: This review contains major spoilers for Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

I had a phase as a teenager where my musical tastes veered toward covers: punk rock versions of old standards, acoustic covers of hard rock classics, and even orchestral arrangements of Top 40 hits. The blend of the foreign and familiar appealed to me at a time when my taste in music was just beginning to expand. When an artist takes another’s work and puts their own spin on it, transforming what a song means or how it works at an emotional level by filtering it through a different lens, the end result can be both compelling and approachable.

The Force Awakens is, essentially, J.J. Abrams’s cover of A New Hope. That’s not a knock. It’s a superb cover, that hits the right notes while still creating something new, and it stands as a genuine achievement that’s all the more notable in light of the franchise’s prior missteps.

Star Wars: The Phantom Menace Is a Cold, Empty Film in a Series Known for its Richness, Excitement, and Warmth

The internet is the land of hyperbole. Everything is either the greatest event in the history of the world or the worst thing to ever happen. So when it came time to watch The Phantom Menace–arguably the most maligned of the already ill-regarded Star Wars prequels–I approached it with optimism. I didn’t love the film when I saw it at twelve, but I didn’t hate it either. Surely the case against it was overstated. Surely there was a charitable interpretation to be made. Surely it couldn’t be that bad.

And then it was.

Make no mistake — The Phantom Menace is an awful film. It’s not the blight on the soul of cinema that its most ardent detractors would have you believe, but it’s not a good movie. In truth, somewhere past the halfway mark, Episode I manages to settle into a groove of mere okayness. There’s a good portion of the film that, separated from the ardor and expectations that come with the Star Wars appellation, would fall into the voluminous “fine but forgettable sci-fi adventure” category, never to be spoken or thought of again.

Unfortunately, The Phantom Menace does labor under those expectations, and the worst elements of the film are front-loaded. The racial stereotypes, the parliamentary procedure, and the bad child acting are all at the forefront in the early going of Episode I. At some point, the movie stumbles its way into a decent-if-unremarkable story about bucking authority and making peace with longstanding rivals to face a common enemy. But it’s a long slog to get there without nearly enough of a payoff.

Star Wars: a Hero Falters when The Empire Strikes Back

The Empire Strikes Back has a reputation for being the darkest of the Star Wars films. In contrast to the triumphant mood at the end of A New Hope, Empire closes with our heroes having been thoroughly defeated and left scrambling. Han is frozen in carbonite, placed in the hands of a bounty hunter, and ferried to the crime boss he’s been trying to avoid for two films. Luke fails in his quest to neutralize Darth Vader and has his hand sliced off for the trouble. What’s more, he learns not only that the man he loathes most in this world is his father, but that the people he trusted–the ones who guided him on this journey–have misled him. And Leia, Lando, Chewbacca, C3PO, and R2-D2 are all lucky to escape with their lives after being imprisoned, strangled, torn apart, and dragged through the muck.

The title “The Empire Strikes Back” could easily have been a simple marketing ploy, something that looked good on movie posters and sounded cool enough to rev up Star Wars’s legions of fans. Instead, it became an animating principle for the film. Empire contrasts the unexpected blow struck by the Rebels in the first film, with the measured counterpunch delivered by The Empire in the second. The ending of Empire sent the message that this would not be the type of series of films where the good guys win every time just because they’re the good guys.

But there’s much more to the movie than that darkness. It’s easy to judge Empire based on where the characters are at the end of the movie, but the route the film takes to bring them to that point is not so much dark as it is meditative, not so much bleak as it is serious, and, if I’m being honest, a bit more uneven in the effort than its predecessor.

Star Wars: The Balance of the Grand and the Intimate in A New Hope

Of all the memorable visual flourishes in the original Star Wars, there are two images that stand out. The first is arguably the most iconic — Luke Skywalker, gazing off at the horizon, as the twin suns set on Tatooine. It represents the promise of adventure, the enormous world that waits beyond the garden gate, and serves as the prelude to his epic journey.

But the second is much simpler. It’s Luke, Leia, and Han, arm-in-arm and filled with joy, as they celebrate their victory over the Empire back at the rebel base. That moment underlines their unlikely friendship, borne out of shared struggles and triumphs, and shows the film’s heart, clearly felt even in the midst of this grand adventure. That contrast is what Star Wars, at least in its original form, comes down to, and what makes the film still so salient and impressive nearly forty years after its release.

Halloween’s Michael Myers and the Terror of What We Can’t Understand

To understand something is to take away its power. A look behind the curtain renders the tricks in front of it less formidable. The mechanical dinosaur isn’t as scary after the director opens it up to show us the gears and pistons that make it move. The things that we understand are less imposing, even if they are beyond our control, because they can be classified, categorized, and broken down into digestible little chunks until they no longer represent the unlimited, terrible possibilities of the unknown.

In Halloween, director John Carpenter never gives the audience a chance to fully understand the monster he crafts in celluloid. He never lets us truly know Michael Myers — what makes him tick, what produced the cold-blooded killer who emerges from the void at the film’s beginning. Indeed, through the character of Dr. Loomis, Carpenter suggests that Michael may very well be something unexplainable, something that cannot be parsed or reduced to understanding. He simply is.

And that’s a sizeable part of what gives Michael Myers so much power on the screen, so much capacity to terrorize and frighten us. Michael stands a step apart from any discernible human thought or feeling. He is simply a force, lurking in the shadows, silent, cold, and methodical as he completes his grisly labors.

Posted in Classic Films, Movies

Tagged Halloween, John Carpenter, Michael Myers, Movie Reviews, Slasher Movies, Uncanny Valley

2 Comments

Is A Nightmare on Elm Street as Scary in 2015 as It Was in 1984?

What makes a work of art a classic in one era and laughable in another? I’ve written before about the Citizen Kane Effect, or the idea that some works that were groundbreaking for their time had such a profound effect on the medium that they essentially became the new standard, to the point that the innovations of the past might appear mundane to the modern eye. But there’s a flipside to this phenomenon — sometimes a work is innovative and interesting for its time, but as the years pass on, the tropes of the genre change, or the grammar and shorthand for how particular ideas are expressed evolve. When this happens, older works can feel miscalibrated or even half-baked to viewers who come to them after their heydey, having grown accustomed to the conventions of follow-on works that build on, and eventually move away from, their hallowed predecessors.

Perhaps this is why, despite my best efforts, I essentially laughed my way through A Nightmare on Elm Street. It’s prudent to go into any work of art, especially those considered landmarks of the genre, with an open mind. While some seminal works may be overpraised, it’s worth the effort to appreciate why something is considered a classic, even if a modern viewer may have trouble connecting with it. But at a certain point, no matter how hard we try, we cannot escape the baggage that we carry into our viewing experiences.

Perhaps it’s naive to expect a horror film to have the same impact thirty years after its debut that it did when it was originally released. And yet, my prelude to A Nightmare on Elm Street was The Exorcist, a film that predated Nightmare by nearly a decade, but was still just as vivid, striking, and scary in the present day as it was to audiences in the seventies. At the same time, my postscript to the film was Nightmare director Wes Craven’s own Scream, released a little more than a decade later, which manages to be both frightening and fun while trafficking in the same tropes that Craven himself helped establish in Kruger’s first slasherrific outing. So what makes the difference? Why is one scary movie chilling and another chuckle-worthy?

Posted in Classic Films, Movies

Tagged Horror Movies, Movie Reviews, Slasher Movies, The Eighties, Wes Craven

5 Comments

Boogie Nights: Depiction, Endorsement, and the Wounded Humanity of P.T. Anderson’s Film

Depiction does not equal endorsement. An artist may explore the depths of something controversial or lurid or profane without giving it their stamp of approval. This is how we defend films, television shows, and other works of art against the myriad pearl-clutchers and watchdog groups who gnash their teeth, gather their pitchforks, and declare that “something must be done.” It’s how we protect the scores of transcendent works about unseemly, unsavory, or otherwise unpalatable personalities who offer compelling narratives, but who may never receive their societally-mandated dose of comeuppance or public shame by the time the story ends.

But here’s a dirty little secret – depiction is much more complicated than either the defenders or the scolds would readily admit.

Make no mistake — the fact that a film simply shows bad behavior, even in seemingly glamorous terms, does not necessarily mean that the director intends it as something to aspire to. The camera itself makes no judgments. Context speaks volumes. But merely pointing a camera at someone or something does still send a message. It says, “This is worth caring about, or at least worth paying attention to.” Aim it at a particular event, or individual, or group of people, and it says theirs is a story worth telling.

Which is to say that when Boogie Nights director Paul Thomas Anderson decided to point his camera at the lightly-fictionalized men and women of the San Fernando Valley porn industry in the 1970s and 1980s, he never truly glamorizes their existence or expresses his unqualified approval for how they live their lives. To the contrary, though the film ends on a note of bittersweet hope, the thrust of the work is how the flash and filth depicted, and the lifestyle that accompanies, thoroughly and pervasively runs these poor folks through the wringer.

The Only Two Deaths in Jurassic World That Mattered

Death is a currency in blockbuster films. Faceless henchman are wiped out indiscriminately. Nameless bystanders are consumed in explosions and buried in rubble. This is the loss of life that makes up the dark matter of the standard action flick — those deaths that are just out of sight or out of focus, but which are intended to give weight to the larger forces of the plot and the choices of the main characters.

Jurassic World embraced this summer movie season truism wholeheartedly. Scores of interchangeable soldiers in the film quickly turn into dinosaur cannon fodder, with little more than blurred security footage and a few ominous beeps to remember them by. Dozens of random park-goers are snatched up by winged dinosaurs in a prehistoric take on The Birds, but it’s always off in the distance, always just for a second, to where the most notable moment in the rabble is Jimmy Buffett shuffling indoors with a pair of margaritas.

But two deaths in Jurassic World stood out, and they were not necessarily the ones I might have predicted when I walked into the theater.

Posted in Movies, Sci-Fi Movies

Tagged CGI, Chris Pratt, Death, Dinosaurs, Jurassic Park, Movie Reviews

2 Comments